“THE GREAT FRENCH photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson famously used the phrase “the decisive moment” to describe the intuitive fraction of a second that separates a timeless photograph from the dozens of less inspired frames surrounding it. This instinct cannot be taught. It isn’t a skill photographer’s acquire as part of their craft. It’s a creative force that defines an individual style. And because Cartier-Bresson had the instinct to trigger his Leica’s rangefinder lens at so many memorable moments, he remains the 20th Century’s most remarkable photojournalist.

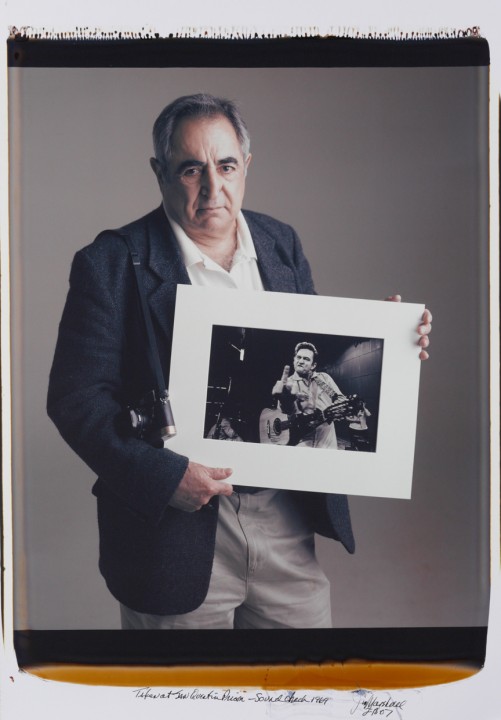

It takes no leap of the imagination to think of another Leica user, Jim Marshall, as the Cartier-Bresson of music photography—or more accurately, musician photography.

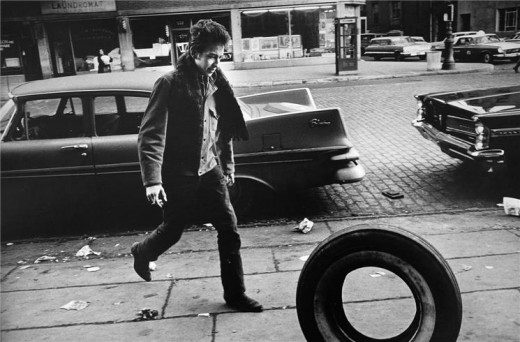

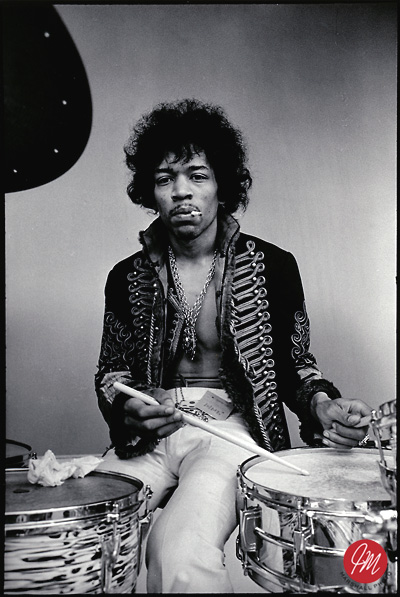

For nearly half-a-century Jim Marshall has captured his own rather remarkable share of “decisive moments.” Whether it was an informal portrait of John Coltrane, a boyish Bob Dylan kicking a tire down a New York street, Hendrix immolating his Strat at Monterey Pop, The Who greeting the sunrise at Woodstock, or Johnny Cash flipping a big F-you at San Quentin, Jim Marshall was there. And during the most extraordinary times yet for popular music, he somehow seemed to be everywhere—that mattered.

But no matter how iconic these and countless other of Jim’s images undoubtedly are, his photographs are always about his subjects, not about making a “Jim Marshall photograph.” Because Jim lived the life alongside his subjects, and never betrayed their trust, he was granted second-to-none access to scores of great musicians. Indeed, it is arguable that the only guy who could have possibly captured certain moments of unguarded intimacy, such as Brian Jones and Jimi Hendrix strolling the Monterey fairgrounds, or Janis Joplin lounging backstage with a bottle of Southern Comfort, is Jim Marshall.

As Jim has said, “…I do see the music. This ‘career’ has never been just a job—it’s been my life.”

Born in Chicago in 1936, Jim Marshall grew up in San Francisco’s Fillmore district. As a boy, he started taking pictures on a Baby Brownie. But after winning a school track meet, and seeing the razor-sharp image of himself crossing the finish line that a spectator had taken with a Leica camera, Marshall’s destiny seemed all but sealed. He acquired his first Leica, an M2, in 1959, for the then-princely sum of $50 down followed by twelve monthly payments of $24 each.

Naturally drawn to San Francisco’s North Beach coffeehouses, Marshall began shooting the beat-poets, artists, and jazz musicians he encountered every day. While in the Air Force, he shot photos of fellow servicemen. After his military stint, trying to launch a career, he photographed dragsters and sports cars. But it was a return to his North Beach roots that brought his first big break, one that would define his path.

It was 1960. While hanging backstage at San Francisco’s Jazz Workshop, Marshall encountered John Coltrane. Then on the verge of his astonishing late-period visionary quest, Coltrane wondered how he might get across the Bay Bridge to Berkeley, where he was to meet with Chronicle music critic Ralph J. Gleason. Seizing the moment, Marshall offered Coltrane a ride to Gleason’s house, where he would fire off nine rolls of film, capturing several classic shots of the soon-to-be tenor legend.

The early ’60s found Jim Marshall in New York, where assignments from record labels such as Atlantic, Columbia, and ABC Paramount, and the magazines Newsweek and The Saturday Evening Post added to his ever increasing reputation, and offered unusual access to folk and jazz musicians. Lesser-known aspects of Marshall’s early work include photojournalism assignments documenting life in Appalachia, and Civil Rights activities in Mississippi.

In 1964, Marshall drove back to San Francisco and moved into a small North Beach apartment. His timing could not have been more perfect.

Rock ’n’ roll was blossoming, and so were Marshall’s talents. As the beat-era’s coffee, booze, and cigarette culture kaleidoscoped into the pot-smoking, acid-dropping hippy movement, San Francisco was becoming the epicenter of America’s counterculture, with a music scene that would soon rival those of London and New York.

As a fixture on the scene, Jim Marshall was there to immortalize local bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother, and Santana long before they were household names. In 1966, Marshall was the only photographer allowed backstage access to what proved to be The Beatles’ final concert at Candlestick Park. A year later, Jim’s photos from the Monterey Pop Festival would become as woven into the lore of that gig as would the breakout performances of Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Otis Redding. Marshall was the first photographer to shoot The Who and Cream in the U.S; he was selected as one of the official photographers of the Woodstock Festival, covered the Rolling Stones ’72 tour for Life magazine, and is the only photographer able to squeeze the friendly rivalry between Janis Joplin and Grace Slick into a single frame.

But as extraordinary as Jim’s lifetime body of work is, for him it all comes back to the music. As he wrote in the introduction to Not Fade Away: “Too much bullshit is written about photographs and music. Let the music move you, whether to a frenzy or a peaceful place. Let it be what you want to hear—not what others say is popular. Let the photograph be one you remember—not for its technique but for its soul. Let it become a part of your life—a part of your past to help shape your future. But most of all, let the music and the photograph be something you love and will always enjoy.””

Source: www.marshallphoto.com