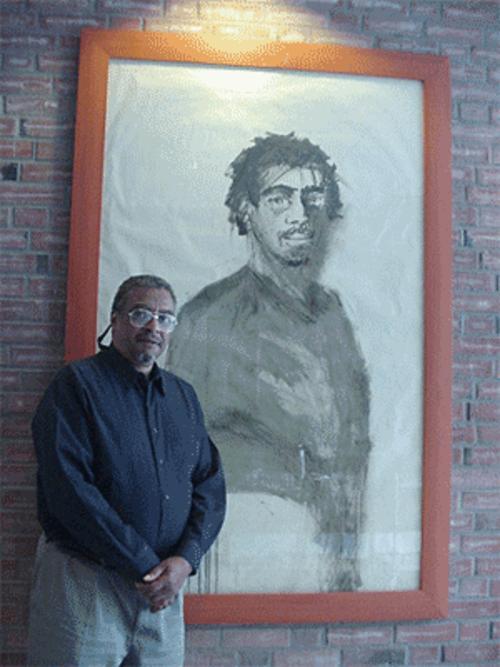

Brooklyn-born Arthur Monroe spent his formative years in New York City. It was during those years that he became a close friend of Charlie Parker, who advised him “to know his axe;” that is, to know his craft, advice that he has adhered to ever since.

Abstract Expressionism was the prevailing American art style in the 1950s and was generally recognized as being the most important modernist art to have occurred after World War II. As a young artist, Arthur Monroe immersed himself in the exciting milieu of the East Village. He had a studio facing that of Willem De Kooning’s, and he hung around the Cedar Street Bar, where he knew some of the most acclaimed Abstract Expressionists, including Franz Klein.

The young Arthur Monroe felt a need to examine non-European sources of visual art and left New York to travel in search of them in Mexico, particularly the sources inherent in the cultures of the Mayans, Zapotecans, Michteans, and Olmecans. He wished to become involved intimately with cultures that offered spiritual, philosophic and aesthetic viewpoints different from his background in the mainstream art world of New York.

Monroe returned to America, first to Big Sur and then to San Francisco during the legendary Beat Era of North Beach in the late 1950s, becoming Proxy-Connection: keep-alive

Cache-Control: max-age=0

important participant in an art scene that included a host of other artists.

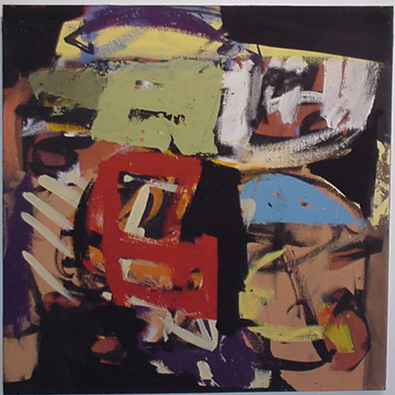

However, Arthur Monroe remained committed to his Abstract Expressionist roots. They have continually provided him with an approach to express himself in his search for new visual truths. He may spend as much as three years on a painting, engaging with it in an interior dialogue and anguishing over each stage of its development. He is unable to paint anything that isn’t an expression of a laboriously-evolved visual turth. Unlike many artists since the 1960s, Monroe eschews drawings as an executional expedient, feeling that this will only reflect what comes off the top of the mind superficially. Initial ideas become extensively transformed as inner truths struggle to be realized.

Nothing is clear ahead of time; Arthur Monroe works more as a scientist asking a myriad of questions before he finds his hypothesis. Many painters bypass this process because they don’t even know that it exists. An artist learns from mistakes, as if the stone knows more about the sculpture than the sculptor himself. Arthur Monroe faces his materials as a challenge; the more he handles them, the more he appreciates what they might do.

Visual innovations are a by-product of the same laborious process of Monroe’s involvement with the medium. A finished painting is unique unto itself and never serves as a prototype for linearly-serialized visual statements. As in the purest era of Abstract Expressionism, extraneous concerns such as ideological stances never dictate the outcome of a painting.

Arthur Monroe remains enchanted by the Abstract Expressionist penchant for large-scale work. He observes that while European Modernist art before World War II was monumental in concept, it wasn’t always large in scale. He was initially attracted to American Abstact Exprssionistic paintings that had the potential to make their impact much greater on the viewer by altering the scale of the work. Monroe continues to find that the space between the painting and the viewer becomes more charged because of the enlarged forms, colors, and brushwork.

Since Arthur Monroe left New York, he has immersed himself in an investigation of non-European cultures extending from Nigeria to the Amazon. He has taken his cue as an artist from T.S. Eliot and Langston Hughes, who said you really can’t write poems until you learn to think in another language. Monroe remains the prototypical underground artist who believes, as Hughes did, that you really don’t understand yourself, your culture, or your art until you understand what is in the person who has the least. Monroe also believes that this applies to the art scene, with each art movement being an important link and none being more important than another.

Ultimately, all artists are part of the chain; these are some of the ideas that Monroe’s art is noursished by, as well as Charlie Parker’s teaching about living and life: “know your axe: know your instrument before you talk with it.”

– Terry St. John